The cold breath of global warming: how winter frost is connected to the warm Arctic

So what to expect from the upcoming winter of 2021–22? Will it be as cold and snowy as the last one? To answer this question, let's go back a year and look at weather history.

February 2021 was very cold, despite a short period of above zero temperatures in the last few days of the month. And not just in Russia: the February frosts in Texas officially became a natural disaster, and Europe was covered with snow. Why is this so? Isn't the climate on our planet getting warmer?

At the request of N+1, one of the main popular science online magazines in Russia, meteorologist Pavel Konstantinov of Lomonosov Moscow State University (MSU) talks about how global warming can lead to record-breaking cold and snowy weather. (Spoiler: Winters, especially in Western Europe, will become more severe than now.)

Pavel Konstantinov, assistant professor of the Department of Meteorology and Climatology at Lomonosov Moscow State University (MSU), Ph.D., one of Windy.app's leading meteorologists

— February 2021 in Moscow was three and a half degrees colder than normal, and the first thaw of the month came only on February 26.

It was cold not only in the Russian capital: the news from freezing Texas makes us remember the stereotypical jokes about the Russian winter, which protected us from the French in the war of 1812, and by the XXI century even learned to attack.

Add to that the snowfalls in Spain, Denmark, and Switzerland, and the Russian capital itself, which over the weekend added a record-breaking half-meter-high snowdrift. There seems to be no shortage of reasons to joke (as well as to worry).

Why is it so cold during global warming

So what is the problem with global warming? It is certainly not a "change of vector to global cooling." As paradoxical as it may sound, in one way or another cold winters in temperate latitudes may be a legitimate consequence of global warming. At least, the physical mechanisms reliably explaining the paradox of cooling in temperate latitudes of Eurasia and North America due to Arctic warming (that is, when the entire Arctic Ocean ice cover melts) are described in the works of the world's leading climatologists — here is the first one about winter atmospheric circulation, and here is the second, titled "Warm Arctic episodes linked with increased frequency of extreme winter weather in the United States."

To put it very simply, the mechanism is as follows: the prevailing westerly winds in our latitudes (geographers call this process "western air masses movement") are caused by the temperature gradient between the cold Arctic and the warm tropical regions. And the stronger the temperature contrast, the more active cyclones carry Atlantic heat to Europe and Russia in winter. That is, the so-called sub-latitudinal air mass movement prevails — when the trajectories of air particles are directed more or less parallel to latitudinal circles.

When the Arctic gets warmer (3–3.5 times faster than the Earth on average), the temperature gradient becomes lower, and the western air masses' movement weakens proportionally. Atmospheric circulation does not tolerate emptiness, so the antagonist of the western movement — the sub-meridional movement of air masses — becomes stronger. It can bring both heat from more southern regions and cold from more northern and inland regions (here it would be appropriate to recall that the Eurasian pole of cold is in the Sakha Republic also known as Yakutia, Russia).

So winters, especially in Western Europe, will become more severe than now. And the general "nervousness" of winter weather will increase. Probably, the winter of 2021 was an excursion into the future of climate with the ice-free Arctic.

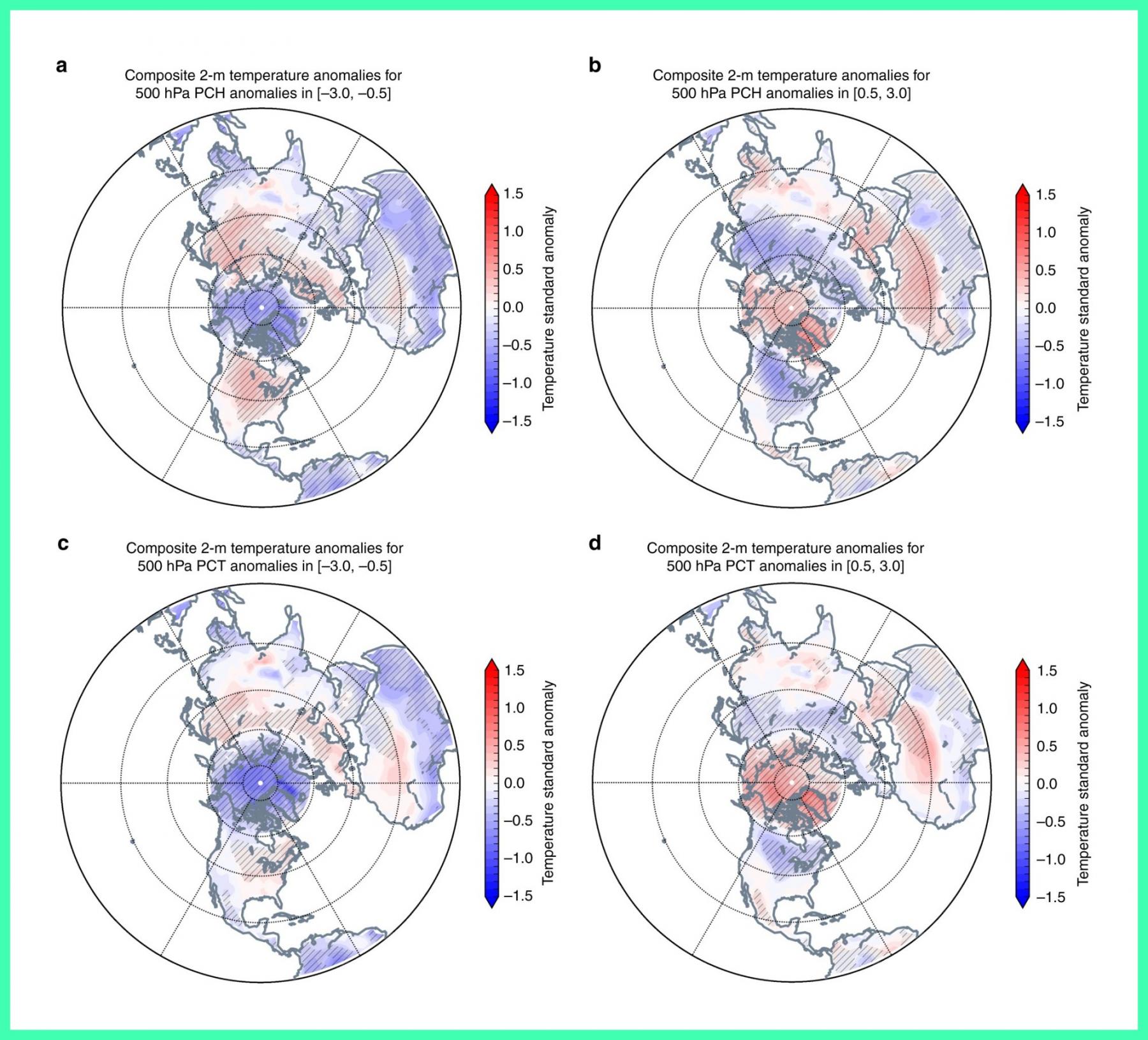

As the Arctic warms the continents become colder. Design: Nature.com

What circulation mechanisms are to blame for the February 2021 touches of frost

Now more about what circulation mechanisms are to blame for the February 2021 touches of frost. That is, let's move from talking about future climates to diagnosing events on a tactical or synoptic scale — as seen on the weather maps used in the weather forecast.

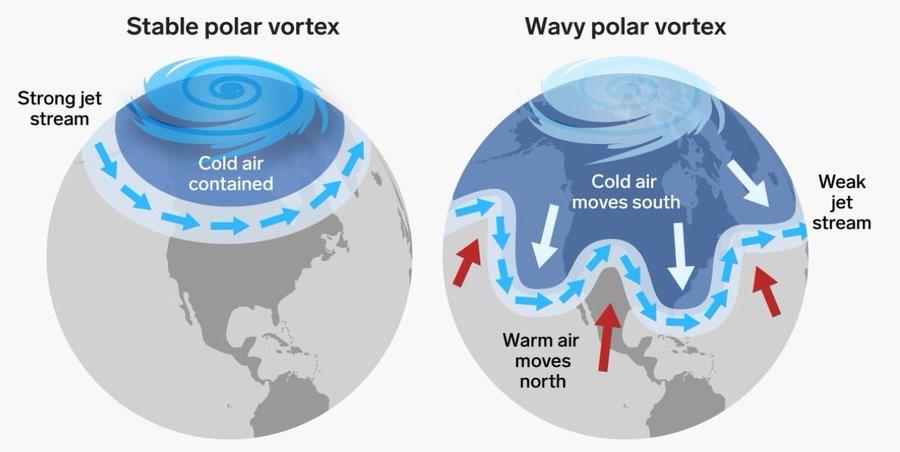

Traditionally, a "polar vortex" (in Russian meteorological tradition, a "Polar circulation cell") forms over the Arctic in winter. This system is relatively autonomous, but not always stable. Sometimes — as happened in 2021 — the vortex sort of breaks into two parts, and they begin to descend southward, causing sharp cooling in the southern latitudes.

Polar vortex. Design: UN Climate Change

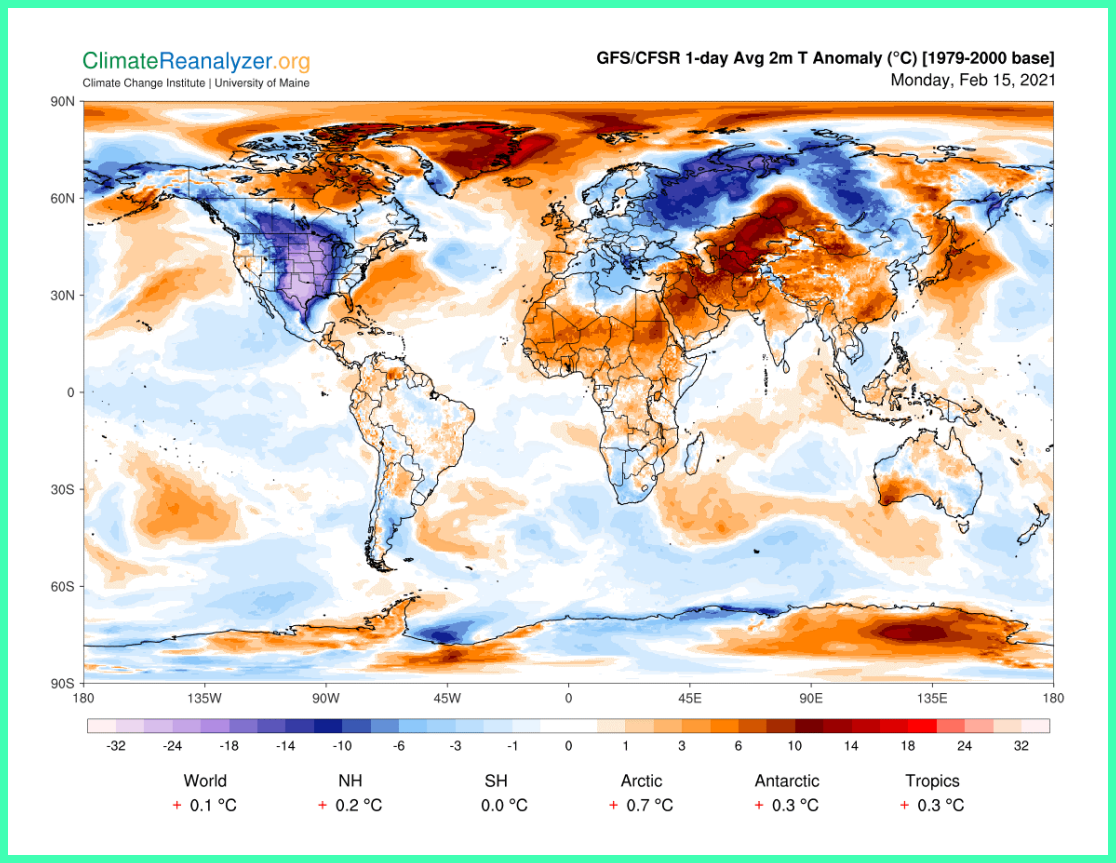

This is usually preceded by a warming in the higher atmospheric layers over the Arctic, the stratosphere — and there was one in 2021 as well. In the second half of February, the cold weather hit Eurasia and North America almost synchronously: here they are, the blue-purple areas on the map below:

Map: Climate Change Institude of the University of Maine, US via ClimateReanalyzer.org

This shift in cyclone paths caused snowfalls and cold weather. At that time, it was too early to call them unprecedented, but in some regions, nevertheless, the weather values were not far from record values. Full statistics of this and other weather phenomenona we are usually able to get later in the year. Then it become clear what place them took in the book of meteorological records for different countries.

Text: Pavel Konstantinov, assistant professor of the Department of Meteorology and Climatology at Lomonosov Moscow State University (MSU), Ph.D., one of Windy.app's leading meteorologists. Read his blog on weather on Instagram

Cover photo: Derek Oyen / Unsplash

You will also find useful

What is safe ice thickness for walking, skiing, ice fishing, and driving

How to read snow forecast to get better experience in winter sports

The three ways to avoid a snowfall when winter hiking the mountains

Latest News

Professional Weather App

Get a detailed online 10 day weather forecast, live worldwide wind map and local weather reports from the most accurate weather models.

Compare spot conditions, ask locals in the app chat, discover meteo lessons, and share your experience in our Windy.app Community.

Be sure with Windy.app.