What is a thunderstorm and how dangerous it is

In this new lesson of the Windy.app Meteorological Textbook (WMT) and newsletter for better weather forecasting you will learn more about thunderstorm and how it works.

What causes a thunderstorm?

Before talking about thundersnow, let’s look at how typical summer thunderstorms form. A thunderstorm is one of the most fascinating atmospheric phenomena but scientists still don’t fully understand the reasons for its occurrence. Leading theories focus around separation of electric charge in a cumulonimbus cloud.

Thunderstorms have very turbulent environments. Through the process of convection in the cloud, huge masses of air, water droplets and ice crystals move around at high speed. These particles are constantly colliding and rub against each other, which leads to electrification: just think of sparks we all get while combing dry hair or removing a fibrous sweater. These sparks are just tiny bolts of lightning.

Each cloud contains particles of different sizes. While the smallest ones cannot be seen with the naked eye, the largest may reach several centimetres in diameter. When they bump into each other, small particles acquire a positive charge, while larger and denser particles become negatively charged.

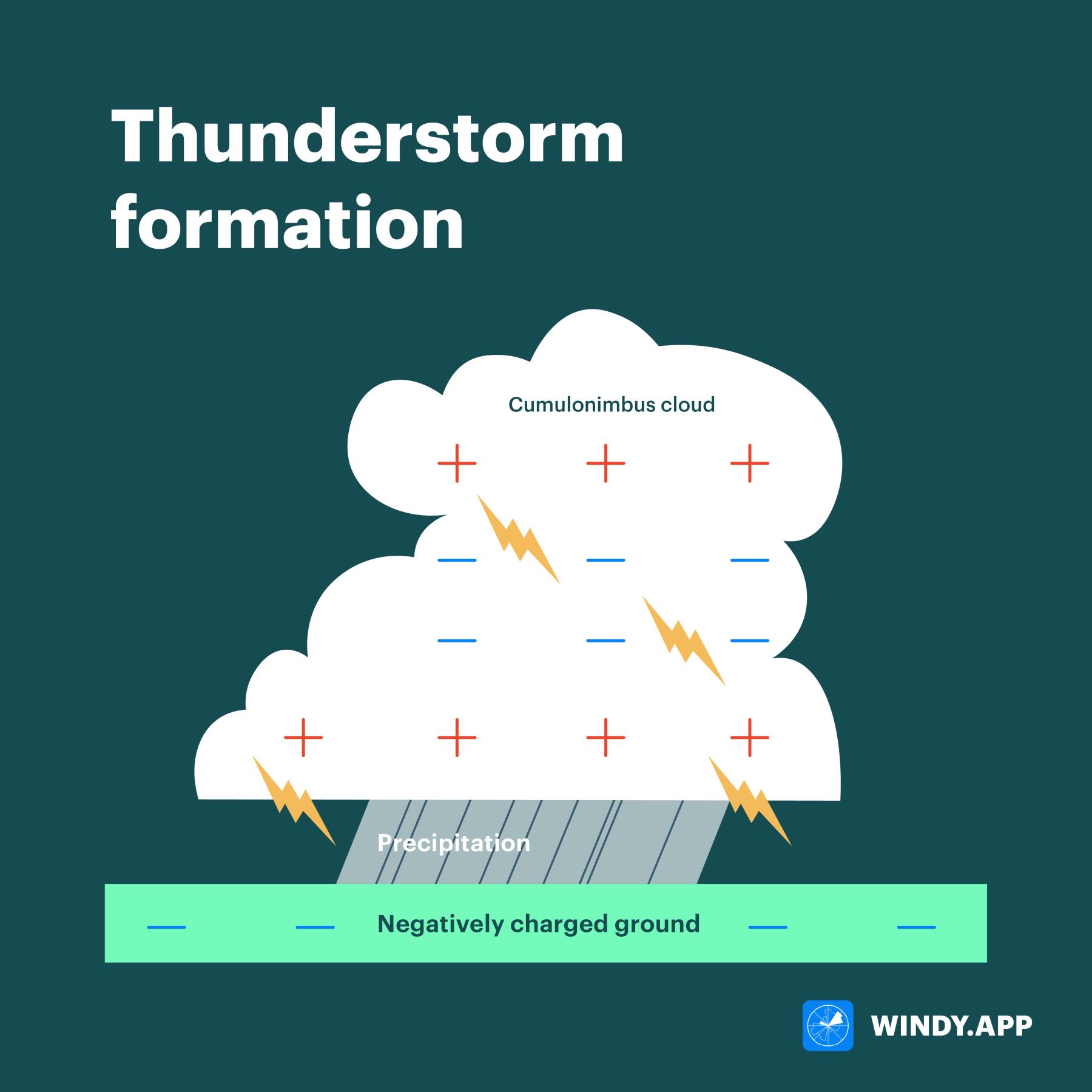

Small particles are lighter than large ones, so they are more easily picked up by convection and end up higher in the cloud than larger ones. The result is that the upper part of the thunderstorm cloud becomes positively charged while the middle part is negatively charged. For some reason, the cloud base is also charged positively. It might be caused by rain. Precipitation forms in the upper, positively charged part of the cloud, but reaches its greatest intensity near the bottom of the thunderstorm cloud while maintaining its charge. Normally, the ground has a slight negative charge.

Thunderstorm formation. Illustration: Valerya Milovanova / Windy.app

In a thunderstorm cloud, positive and negative charges separate into two pools and should produce electricity. However, the atmosphere is a very good insulator that inhibits electric flow, so a huge amount of charge starts to build up, generating voltages up to 5 million times higher than in the domestic electrical outlet! When that charge threshold is reached, or areas with different charges collide, lightning willoccur. The charge will almost instantly move from the area of positive values to the area of negative values, or vice versa. This is accompanied by a bright flash of visible light (due to the heating of the air around the lightning) and thunder (caused by the rapid expansion of the air as it heats up).

What is the difference between a thunderstorm and thundersnow?

Frankly speaking, they are incredibly similar. Summer clouds are composed of ice crystals and water droplets, while in winter they are just made up of ice crystals. However, the formation of a thunderstorm requires particles of different sizes. But while sizes matter, cloud composition is irrelevant. Similarly, it doesn’t matter whether it is raining or snowing.

Why are thundersnows so rare?

They are quite rare because in winter atmospheric activity is significantly weaker than in summer. The ground is cool and rarely heated by the sun. In these conditions, the upward flow of air is usually too weak for the separation of electric charge. Another reason is the density of cold air which can’t hold water vapour required for the formation of cloud particles. Fewer cloud particles create less friction, and, as a result, the chances of thundersnows are very low.

Sometimes it takes several ingredients to come together at the right time during the winter for thundersnow to occur:

- Thundersnow occurs on a very active atmospheric front where the air rises fast enough for the particles to bump into each other and separate by size. The air temperature should not be too low, so that there are enough cloud particles.

- The so-called lake effect thundersnow occurs after a cold air front passes over relatively warm water. The air above the water is sufficiently saturated with water vapour and too warm for winter. When cold winter air passes over the water, active convection helps in formation of cumulonimbus clouds. Then the clouds hit a stretch of cold ground, it starts snowing and within the cloud one can see a spectacle of thunder and lightning.

Where can you see thundersnow?

Thundersnow on an active atmospheric front can be seen anywhere but active fronts in winter are exceptionally rare. Many people living in cold countries with snowy winters may never see thundersnow. The south region of Brazil registered episodes of thundersnow several times, and in early 2021 they were recorded in Europe. The probability of seeing them is slightly higher in the mountains than on a plain.

Lake effect thundersnow typically occurs near large lakes and in coastal areas. There aren’t too many suitable places bearing in mind that a warm water reservoir should be close to cold land. Typically, in winter it is either rather warm on the coast, or the water cools down and gets covered with ice. Thundersnow with lake-effect snow is more common in the Great Lakes area of the United States and in Japan, where they sometimes occur several times per winter season.

Text: Windy.app team

Illustration: Valerya Milovanova, an illustrator with a degree from the British Higher School of Art an Design (BHSAD) of Universal University

Cover photo: Frankie Lopez / Unsplash

You will also find useful

Latest News

Professional Weather App

Get a detailed online 10 day weather forecast, live worldwide wind map and local weather reports from the most accurate weather models.

Compare spot conditions, ask locals in the app chat, discover meteo lessons, and share your experience in our Windy.app Community.

Be sure with Windy.app.