Where Do 800-Kilometer-Long Lightning Bolts Come From?

Everyone knows the expression «a bolt from out of the blue.» But did you know that lightning can actually strike hundreds of kilometers away from the core of a thunderstorm — even where there’s no rain at all? How many people know this? Half? A third? We don’t know for sure — but today we’ll explain where and when such lightning can occur, to improve those odds.

How Lightning Forms

For cumulonimbus clouds — thunderclouds — to form, you need two main ingredients: intense evaporation and strong upward air currents (updrafts). Rising water vapor cools and condenses on tiny particles in the atmosphere, turning back into liquid droplets.

The more moisture that condenses, the greater the chance the cloud will develop into a thunderstorm. Inside the cloud, droplets and ice particles constantly collide and rub against each other — a bit like rubbing a balloon against your hair — which causes electrons to move.

Lightning is simply that: the rapid movement of electrons — either between different parts of a cloud, or between the cloud and the ground.

Photo: Edward Mitchell

What Happens During a Lightning Strike

The movement of electrons is so fast and energetic that collisions along the way cause other particles to emit light and heat the surrounding air — up to 30,000°C (54,000°F)! The air expands explosively, creating a shock wave that we hear as thunder.

A single cumulonimbus cloud, or a part of one capable of sustaining a storm, is called a cell. Cells can merge, forming larger thunderstorm clusters. And when this process happens over a huge area — where vast amounts of moisture evaporate — the result is a gigantic storm system known as a mesoscale convective system. (Think of it as the Megazord version of a thunderstorm.)

Meso... what?

Mesoscale Convective System, or MCS, is a sprawling thunderstorm complex made up of multiple cells, often stretching over 100 kilometers (60 miles) or more. Unlike a typical thunderstorm that lasts up to an hour, an MCS can persist for several hours and cover multiple regions.

For an MCS to form, moisture must continue to evaporate even at night — not just during the day. This usually happens when the sun heats the ground significantly, and the temperature remains warm after sunset. MCSs often form along jet streams — strong upper-level winds that help storms spread over large distances.

Everything about an MCS is on a grander scale: intense rainfall (sometimes up to half the annual norm in one event), frequent lightning, powerful gusts, and even tornadoes.

And sometimes, they produce megaflashes — lightning bolts stretching for hundreds of kilometers, as long as the International Space Station itself.

A horizontal lightning illuminating a cloud from the inside out. Photo: Jessie Eastland

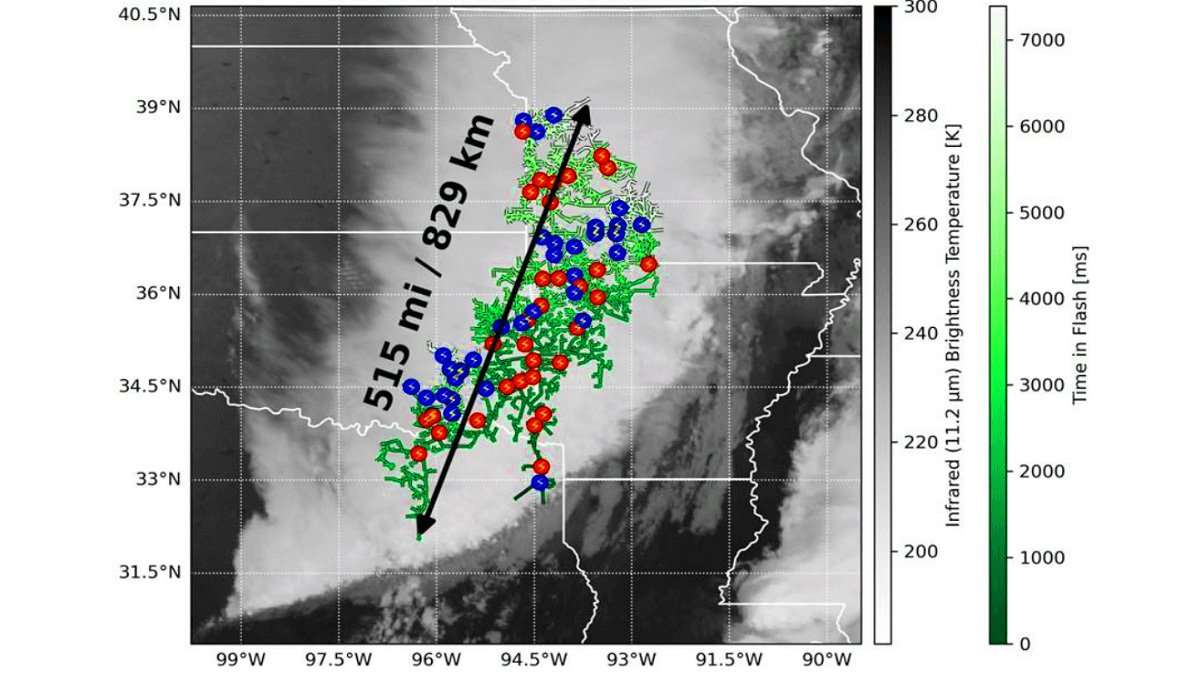

In 2025, scientists discovered the longest lightning bolt ever captured — found in archived satellite images. It was a horizontal megaflash spanning 829 kilometers (515 miles) from Texas to Kansas City in 2017.

That’s a distance you’d cover in about eight hours by car, or one and a half hours by plane.

The flash lasted seven seconds — and was only detected thanks to satellite instruments, since ground-based stations missed it entirely. Multiple branches of the lightning that grew along the way are marked with green. Photo: NOAA

Megaflashes occur when the initial lightning channel connects with another conductive path in a different part of the cloud — and then another, and another — until electrons have traveled hundreds of kilometers, branching out like a glowing tree reaching for light.

Where is it possible to encounter a megaflash?

Because a megaflash can sometimes extend beyond the cloud and reach the ground, it can be dangerous even in areas that seem calm — where it’s just overcast, with no sign of a storm. You might suddenly see lightning strike nearby, though the storm itself is hundreds of kilometers away.

That’s why meteorologists carefully monitor the development of MCSs and issue timely warnings for affected regions.

MCSs are most common in the Great Plains of the United States, from May to September, the peak thunderstorm season. The previous record megaflash, spanning 768 kilometers, was also recorded in this region in 2020.

In Europe, MCSs typically occur in late August and September, especially over the western Mediterranean. They are also observed between Australia and Oceania, across Indonesia, and southeast of Brazil.

Staying Safe During Thunderstorms

The safest place during lightning activity is a sturdy building with proper electrical wiring and plumbing. If that’s not an option, seek shelter in a fully enclosed car with a metal roof.

Avoid open structures such as beach shelters, bus stops, and convertibles — they won’t protect you.

Of course, the chance of being struck by a megaflash from hundreds of kilometers away is extremely small — roughly as likely as being hit by a falling piano, a meteorite, or achieving world peace. Still, if you follow basic safety guidelines and pay attention to weather alerts, you’ll be fine — and a «bolt from the blue» won’t catch you off guard.

Forecasting MCS in Windy. app

MCSs are serious weather systems — and it’s best to know about them in advance. Windy. app provides several tools to track and forecast them.

- Weather radar layer: shows areas of heavy precipitation (yellow and red on the map). A large, dense area often indicates an MCS.

- 2-hour precipitation forecast: helps you see how the storm is moving and changing in intensity.

- HRRR model (for the US): updates every hour with a 2-day forecast based on radar data, useful for tracking MCS «plans.»

- CAPE index: if values exceed 800–1000 J/kg, thunderstorms are likely.

Text: Jason Bright, a journalist and a traveller.

Cover photo: Jandré van der Walt / Unsplash

Read more:

Latest News

Professional Weather App

Get a detailed online 10 day weather forecast, live worldwide wind map and local weather reports from the most accurate weather models.

Compare spot conditions, ask locals in the app chat, discover meteo lessons, and share your experience in our Windy.app Community.

Be sure with Windy.app.