How do Mountain and valley winds form

The mountains have their own 'breezes'. They are called mountain and valley winds. In this new lesson of the Windy.app Meteorological Textbook (WMT) and newsletter for better weather forecasting you will learn more about what valley wind is and how it works.

'Mountain Breezes'

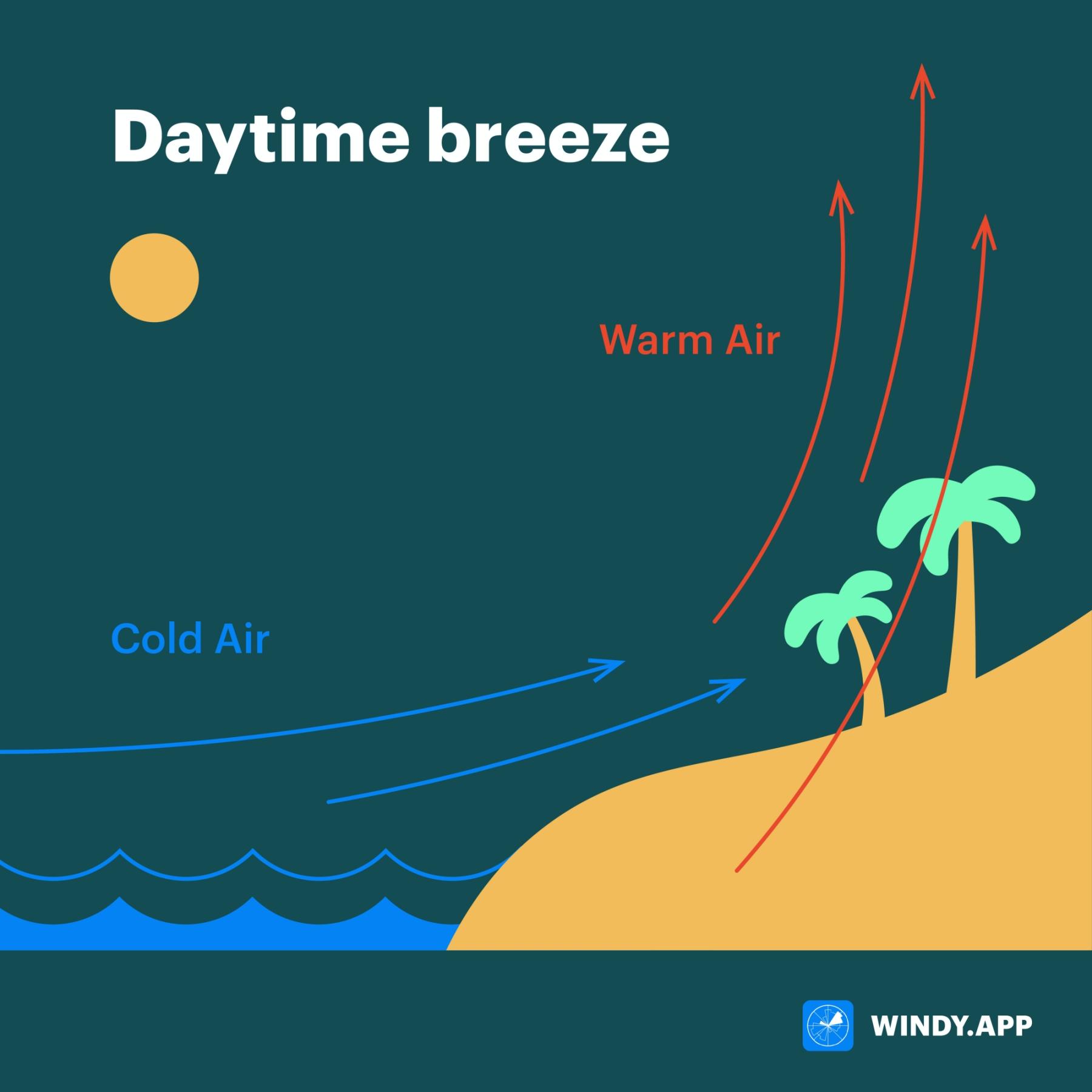

Let’s recall the ordinary sea breeze. This wind blows from the sea to the shore during the day and in the opposite direction at night. During the day the shore warms up, the air rises there, and the cool air from the sea takes its place. By evening, the land cools down, while the sea, on the contrary, warms up and retains heat. So at night the wind blows in the other direction.

While near the sea the breeze mostly blows horizontally, in the mountains a similar wind blows along the slope. It works like this: in the mountains, the air warms during the day and rises from the valley up the slopes, and at night it cools and descends from high places into the valley.

Daytime breeze mechanics. Illustration: Valerya Milovanova / Windy.app

How does wind form in the mountains?

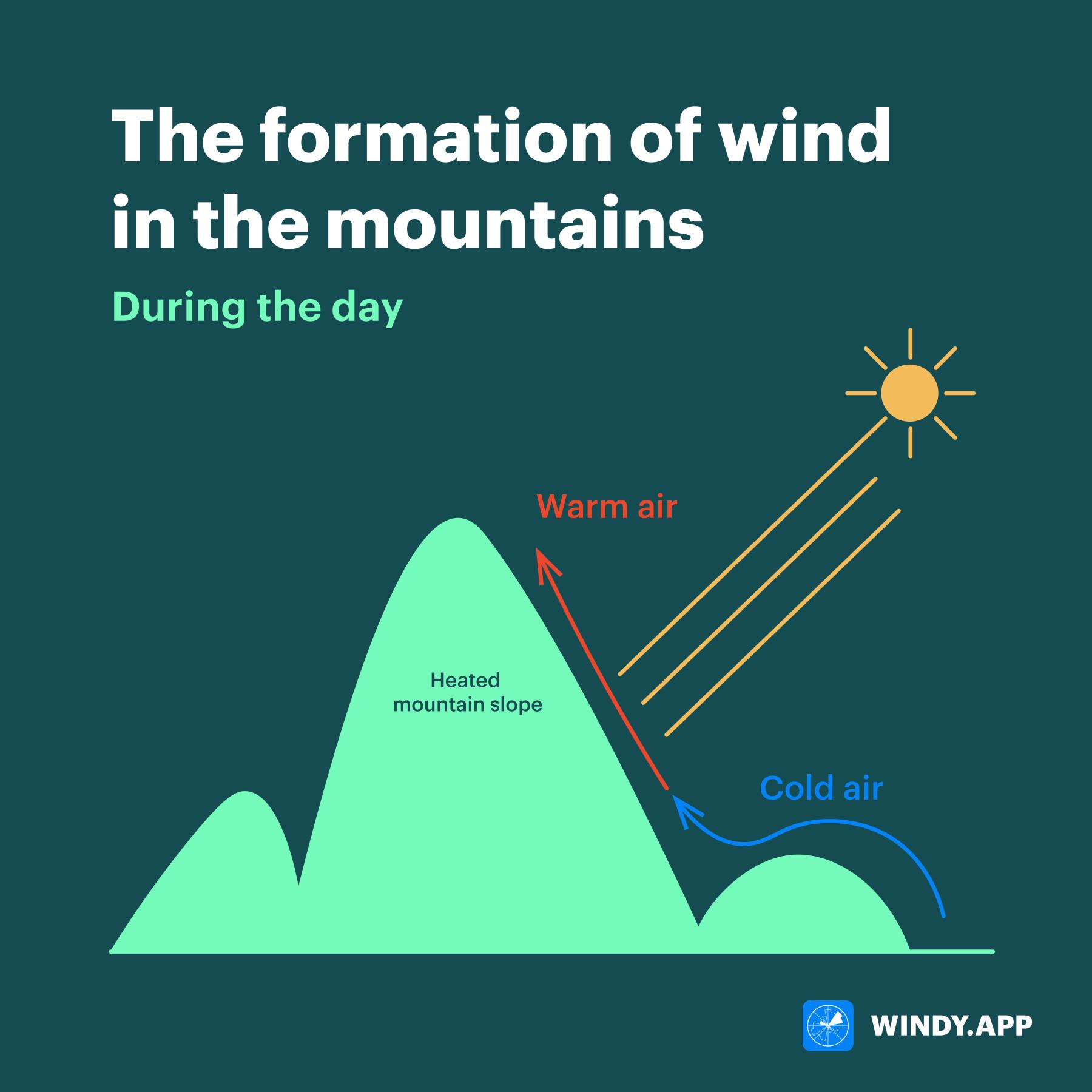

During the day, the sun’s rays strongly heat the mountain slopes. The slopes give their heat to the air, but only the air immediately adjacent to the mountain heats well. And the air at a distance from the mountain stays cold. Warm air is lighter than cold air. It is pushed upward by the cold air and pressed against the mountain by the cold air. As a result, the warm air begins to blow upward along the slope.

Why does warm air blow upward along the slope and not rise vertically upward? The fact is that the warm air rises vertically when it is SURROUNDED by the cold air (which forces it up). If the cold air is on only one side, then it displaces warm air, but at the same time — presses it to the mountain.

This wind blowing up the slope is called anabatic (from the Greek anabaino — to rise).

The formation of wind in the mountain during the day. Illustration: Valerya Milovanova / Windy.app

To continue the analogy with the breeze, the mountains and the air near them play the role of the shore, and the air at some distance from the mountains plays the role of water.

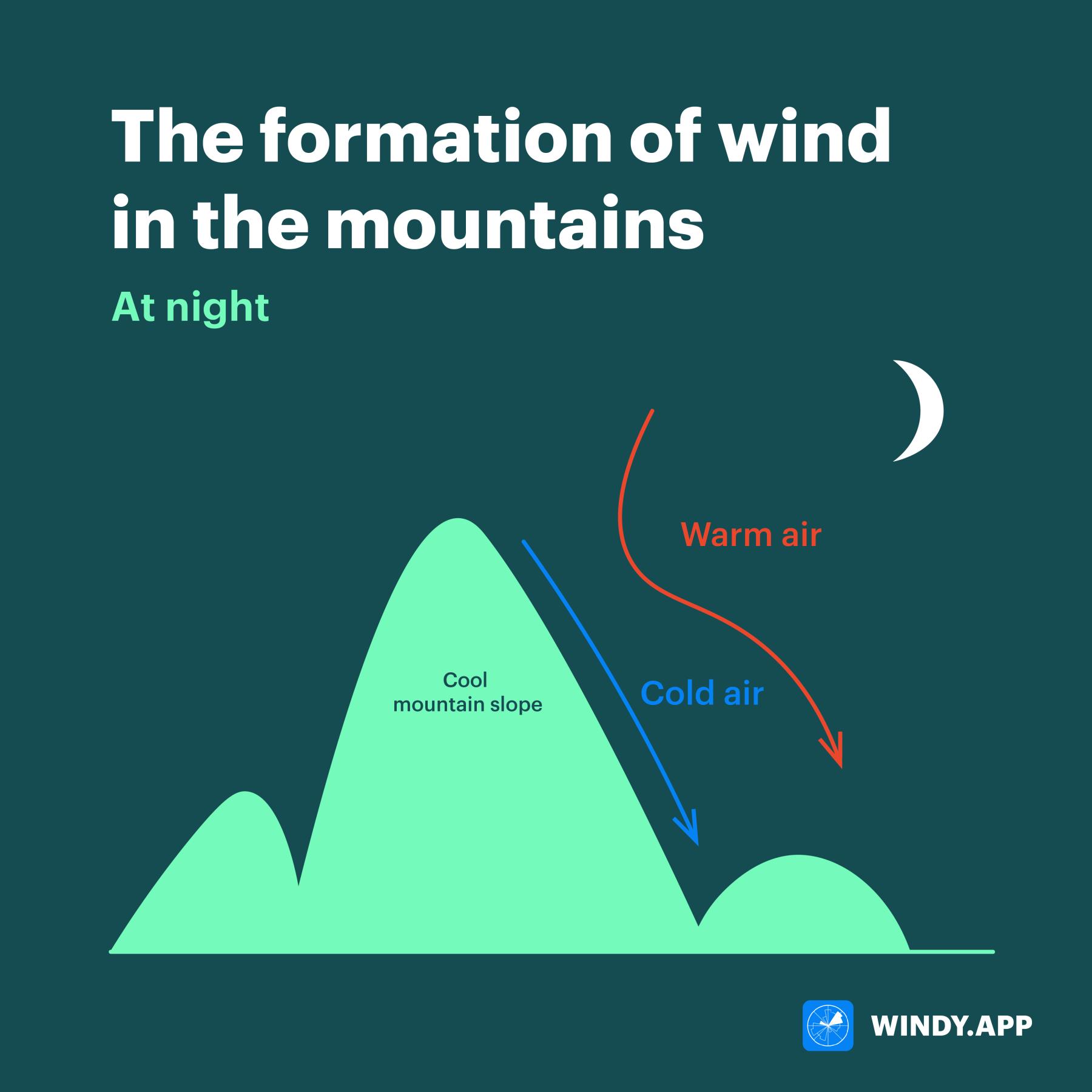

At night, the slopes (like the shore) cool quickly, and the air cools slowly (it has water in it, which holds heat for a long time). However, the air that is directly adjacent to the cold mountains cools faster, which means it gets heavier and begins to flow down the cooler slopes, surrounded by warmer air. Such cold winds, directed down the slopes, are called katabatic (from the Greek κατάβασις, katabasis — descent, decline).

The formation of wind in the mountain at night. Illustration: Valerya Milovanova / Windy.app

Note: Katabatic winds can also exist without anabatic winds. This is the case on glaciers, where a cold glacier cools the air around the clock, which as a result continually flows down.

Both of these winds, katabatic and anabatic, together make up the mountain-valley circulation. These winds are mainly observed in the warm season.

By the way, on mountainous coasts, the mountain-valley circulation merges with the breeze circulation — in this case they mutually reinforce each other.

Text: Windy.app team

Illustration: Valerya Milovanova, an illustrator with a degree from the British Higher School of Art an Design (BHSAD) of Universal University

Cover photo: Unsplash

You will also find useful

How Jet streams work? Simple explanation

Latest News

Professional Weather App

Get a detailed online 10 day weather forecast, live worldwide wind map and local weather reports from the most accurate weather models.

Compare spot conditions, ask locals in the app chat, discover meteo lessons, and share your experience in our Windy.app Community.

Be sure with Windy.app.