How does the mistral form

The mistral is a strong, cold, northwesterly wind that blows from southern France into the Gulf of Lion in the northern Mediterranean. In this new lesson of the Windy.app Meteorological Textbook (WMT) and newsletter for better weather forecasting you will learn more about mistral and how it works.

Where is the mistral observed?

The mistral is observed on the Mediterranean coast of France. It comes there, namely to the Gulf of Lion, from the north. It is a dry, cold, and very strong wind.

Its speed often exceeds 66 km/h (41 miles per hour), and in some places, it can reach 180 km/h (112 miles per hour). Most often, 175 days a year, the mistral is observed in Marseille. Not surprisingly, due to the mistral, there are no windows and doorways on the north side of the houses of the city.

The territory and water area where the mistral can be observed, and the main wind directions

How does the mistral appear?

Because it is a local wind, it is determined by the terrain. First, let’s outline the general scheme of this wind’s appearance, and then we will specify all the details.

The scheme:

- The synoptic situation is such that there is a current heading to the south to France, towards the foothills of the Alps.

- Reaching them, the stream is fed by the cold mountain air. The heavy cold air rolls down from the mountains towards the sea. Rolling down, the wind speeds up.

- Then the air passes through narrow places in the terrain — mountain passes and river valleys — and there it accelerates even more.

- Finally, the wind accelerates further above the Gulf of Lion.

Now, the details.

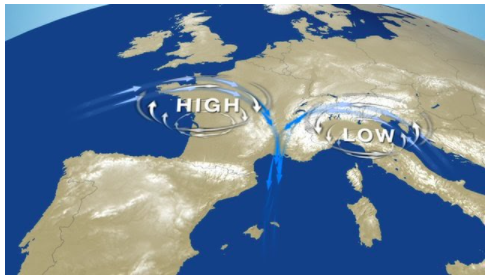

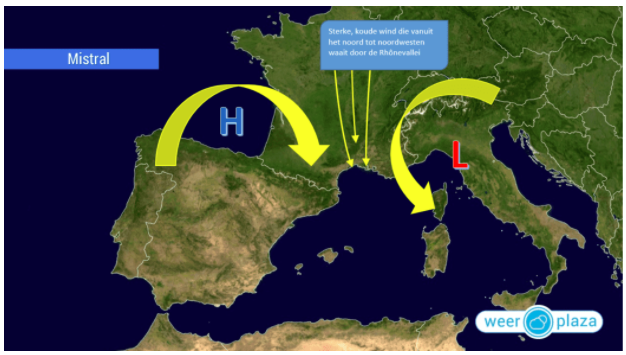

At the first stage, the synoptic situation is responsible for the appearance of the mistral. For the mistral, the situation is favorable when an anticyclone appears over the Bay of Biscay, in the west of France, and a cyclone appears over the Gulf of Genoa, in southern Italy.

Before the mistral, a small cyclone rises over the Gulf of Genoa in southern Italy, and an anticyclone appears over the Bay of Biscay in western France. Illustration: Valerya Milovanova / Windy.app

An important reminder

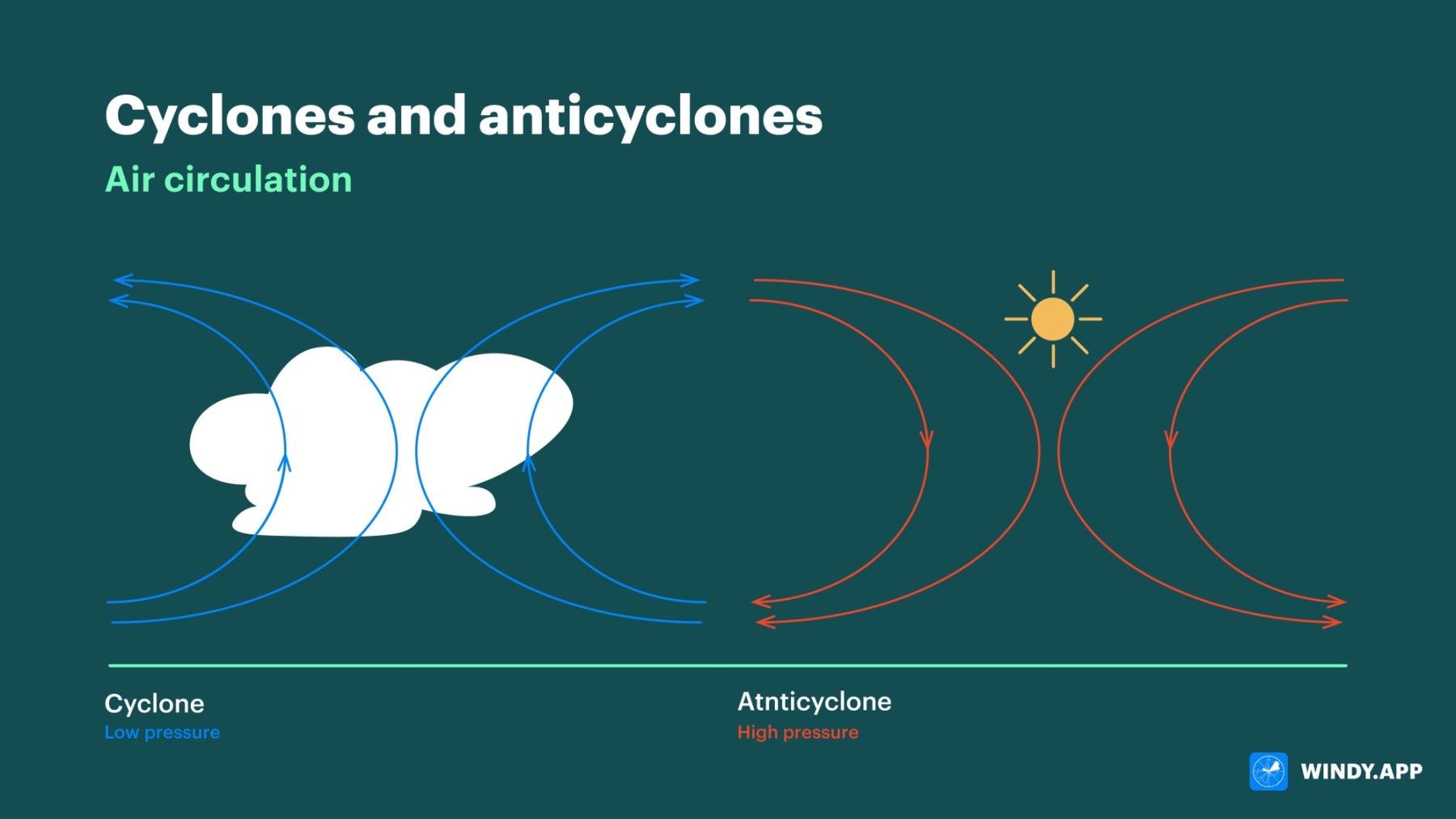

An anticyclone is a zone with high pressure. In this zone, the air descends and then spreads over the sea or land surface. When spreading, it heads to a low-pressure zone, i.e. towards a cyclone.

The air coming from the anticyclone rises upwards inside the cyclone.

Air circulation in cyclones and anticyclones. Illustration: Valerya Milovanova / Windy.app

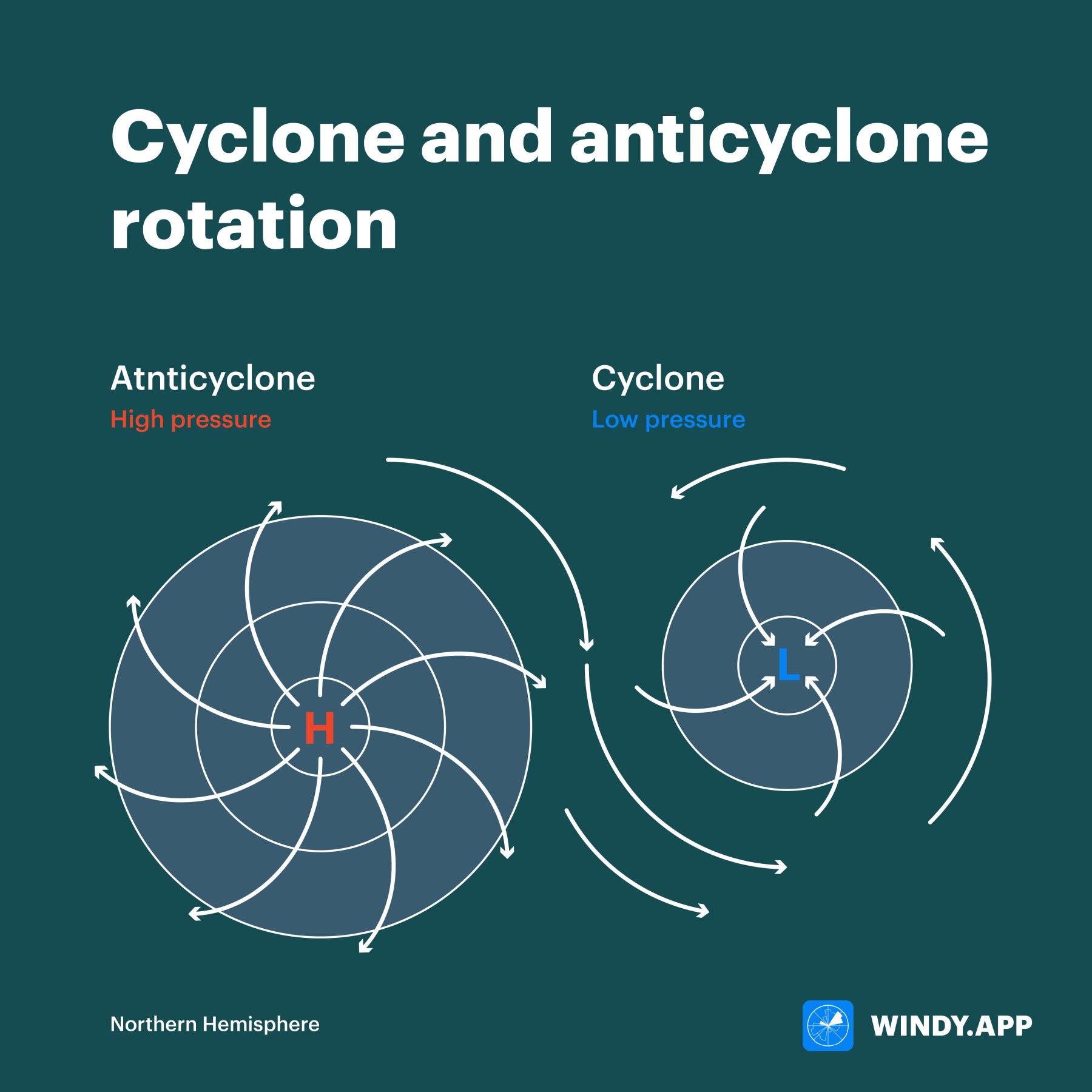

The anticyclone and the cyclone also rotate. In the Northern Hemisphere, the cyclone spins in a counterclockwise direction, and the anticyclone spins in a clockwise direction (in the Southern Hemisphere, it is vice versa).

Cyclone (right) and anticyclone (left) rotation in the Northern Hemisphere. Illustration: Valerya Milovanova / Windy.app

In the case of the mistral over the Bay of Biscay, the air descends, and at the surface it follows the path of rotation towards the Mediterranean Sea across France. And this flow becomes the starting point of the mistral.

This flow becomes the starting point of the mistral

So why does an anticyclone appear regularly over the Bay of Biscay and a cyclone over the Gulf of Genoa?

With the anticyclone, everything is simple. The Bay of Biscay is close to the tropics, where the pressure is always high. It is high because the air that has risen from the heated equator descends in these latitudes. So there is always an anticyclone near the Bay. It can change its position a little, and sometimes it enters the Bay of Biscay.

Why does the Genoa cyclone occur? There may be different mechanisms in different seasons of the year. The mistral is most often observed in winter, so we will consider the mechanism that most often works in winter.

It is related to the temperature contrasts between the sea and mountains. The air above the Gulf of Genoa is relatively warm because the sea is warmer than the land during the cold season. The warm sea air borders cold mountain air to the north.

There are mountains with cold air to the north of the relatively warm Gulf of Genoa.

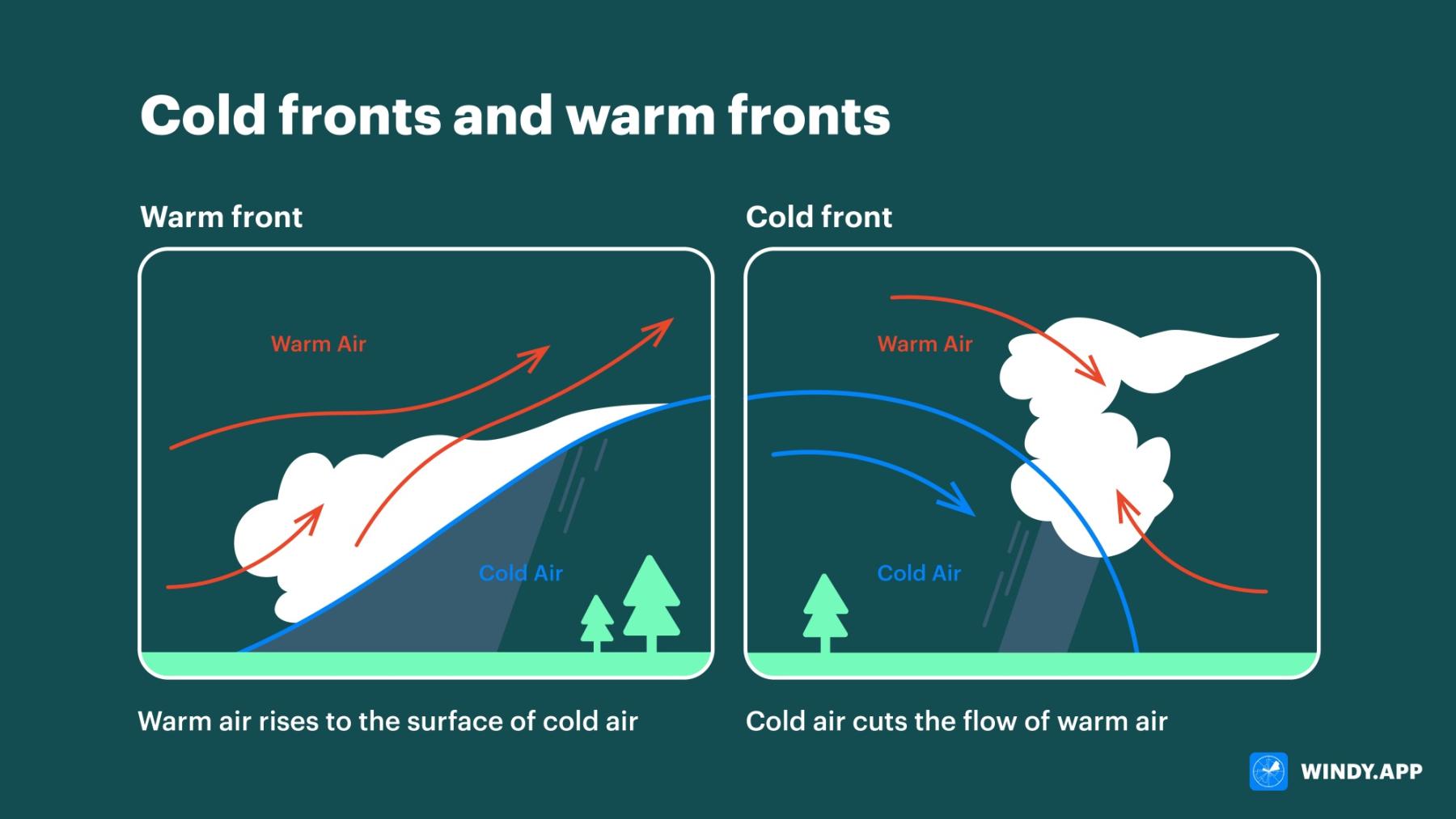

That is, there is initially a clear border that separates the cold and warm air — a front. But currents of cold air descend from the mountains to the sea. They get to the Bay, and the border becomes less clear.

Now the cold air is moving towards the warm air, to the south, and the warm air is also beginning to move towards the cold air, to the north.

Cold and warm weather fronts. Illustration: Valerya Milovanova / Windy.app

In such cases, it is said that a wave appears at the front. Thus a cyclone appears in the Gulf of Genoa.

Then, air from the ’Biscay’ anticyclone flows towards the Genoa cyclone. So, the synoptic situation provokes the appearance of a current going towards the Mediterranean Sea.

Then, the wind accelerates. Why?

In winter, the moving air is cold and heavy enough. The current meets mountains and hills close to the south of France. In the mountains, the cold air from the peaks is additionally drawn into the current. The air is even heavier, and then it rolls down the slopes. The heavy air accelerates due to gravity. This is how the mistral starts to gain speed.

The mistral passes through the mountainous areas in the south of France, and this accelerates it

At any time of the year, when a current passes through narrow places in the terrain — mountain passes and river valleys — it experiences forced compression. Compression means a reduction of the contact area with the hard surface, the terrain. And the less contact, the less friction that slows down the current.

In other words, the mistral in the south of France passes through so-called ’acceleration zones’ and its speed constantly increases there! The mistral reaches the highest speed (180 km/h or 112 miles per hour) in the valley of the French river Rhone.

A peculiarity!

The air’s descent from the mountains according to the laws of thermodynamics should lead to the so-called adiabatic heating of the air. Why is the mistral cold?

This can be explained by the fact that initially very cold air spreads across the mountain ranges (you can see that it comes from the north), and even if heating occurs, the air remains cold for more southern places where it comes.

But it is also important that if the air is cold, it is dense, and therefore its descent from the mountain is sharp and fast, and in such conditions, adiabatic heating almost does not occur. Then, the wind accelerates even more above water, because the friction force decreases sharply.

These are the features that make the mistral so strong, and this makes it dangerous and destructive. But there is also a positive side. The mistral constantly disperses clouds and brings dry air, making the south of France famous for its cloudless weather.

The low clouds formed before the mistral are carried away by the current, and then no new clouds are formed in the dry air. Similar winds blow in other places on our planet. However, they have some peculiarities and are called differently: bora and nord.

Text: Windy.app team

Illustrations: Valerya Milovanova, an illustrator with a degree from the British Higher School of Art an Design (BHSAD) of Universal University

Cover photo: Unsplash

You will also find useful

Latest News

Professional Weather App

Get a detailed online 10 day weather forecast, live worldwide wind map and local weather reports from the most accurate weather models.

Compare spot conditions, ask locals in the app chat, discover meteo lessons, and share your experience in our Windy.app Community.

Be sure with Windy.app.