How does El Niño work

El Niño is a mighty weather phenomenon, a warming of the water surface in the eastern Pacific Ocean, which has a significant effect on the climate. In this new lesson of the Windy.app Meteorological Textbook (WMT) and newsletter for better weather forecasting you will learn more about what El Niño is and how it works.

Boy and girl

Once in a few years in the Pacific Ocean, the surface layer of water warms up considerably and for a long time. Until the 20th century, sailors believed that there is a warm current, calling it El Niño — ’a boy’ in Spanish.

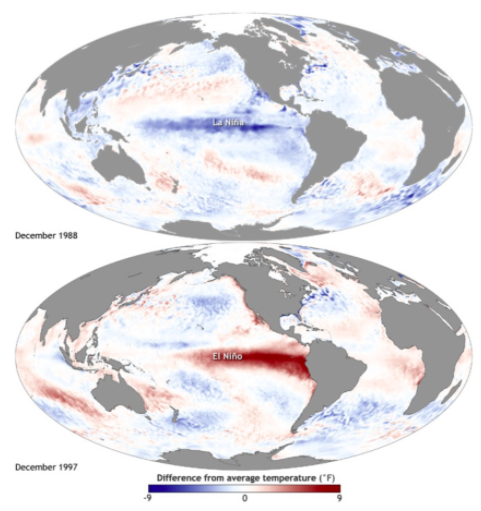

In the same region, sometimes the water gets noticeably cold on the contrary, and this phenomenon was called La Niña, ’a girl’. Later it turned out that El Niño and La Niña are two phases of the same process called Southern Oscillation.

For a long time people ignored this phenomenon, and only at the end of the 20th century, computer modeling allowed to see that Southern Oscillation affects temperature, precipitation and weather almost all over the Earth.

The El Niño phase attracted special attention as its consequences can be disastrous.

Deviation from the average water temperature at the ocean surface during the La Niña phenomenon in 1988 and El Niño in 1997 (in degrees Fahrenheit)

How does El Niño appear

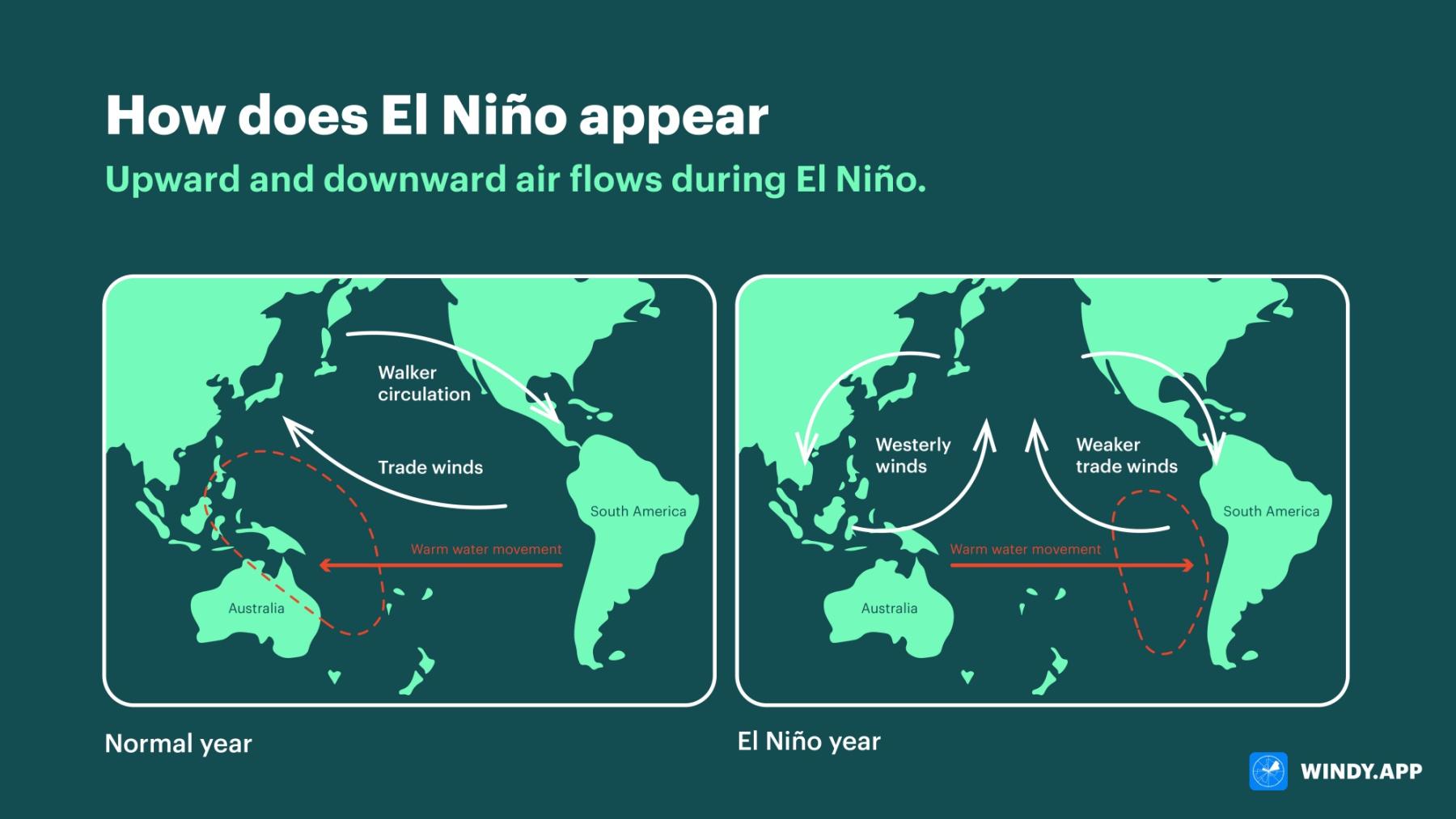

Usually winds near the water surface in the equatorial part of the Pacific Ocean blow to the west, moving the sun warmed water to the region of Indonesia and providing high humidity there.

In the east of the ocean, near the coasts of equatorial South America, on the contrary, the air is very dry, so deserts have formed there. Winds there drive warm water to the west — from the shore, and it is replaced by nutrient-rich cold water from the bottom, which feeds local fish.

Why do the winds at the equator blow to the west?

The equator receives most of the sun’s heat, so the water warms up more there. Warm air starts to rise up, as it is lighter than the cold air hanging above it. Because of this, there’s a low pressure zone near the water surface, which the air from the north and south tries to fill. This is how equatorial wind is born. It’s deflected to the west by the Earth’s rotation force, the Coriolis effect.

But sometimes — scientists can not yet say exactly why — equatorial winds in the east and center of the Pacific Ocean noticeably increase or weaken for weeks or entire months. And then everything changes.

When the winds become weaker or start blowing in the opposite direction, the sun warmed layer of water moves more slowly to the west. As a result, warm water accumulates in the eastern and central Pacific Ocean and the water heats up the air more strongly.

Upward and downward air flows during El Niño. Illustration: Valerya Milovanova / Windy.app

As warm air always tends upwards as it is lighter than cold air, more upward flows of warm humid air appear in the eastern and central part of the ocean than usual. And this, in turn, leads to the formation of clouds and more frequent rains.

El Niño occurs irregularly — two to seven years may pass between the phenomena — and warming-up lasts from five months to two years. During this time, El Niño manages to influence the weather in different parts of the world.

The consequences of El Niño

The specific consequences depend on the season and the strength of El Niño itself.

One thing always happens: rains in the western Pacific Ocean, in the region of Indonesia, become weaker and rare, causing drought. And in the east — i.e. on the west coast of South America, in Peru and Ecuador — due to overheated water, the rains on the contrary turn out to be long and heavy, even in deserts, and sometimes cause floods.

Off the coast of Peru and Ecuador, fish begin to starve and die en masse: the weakened wind stops the rise of nutrient-rich cold water from the bottom, and the water warms up even more.

Fish-eating birds also starve to death. Fishermen have nothing to catch, which together with the problems that prolonged rains bring to agriculture, visibly affects the economies of local countries. Agriculture is also in crisis in the Indonesian region, but because of the drought, not the rains.

El Niño does not hurt everyone — in some regions, the phenomenon even helps people. Less significant increase in air humidity than in South America is also noticeable in eastern equatorial Africa (due to rising air currents and subsequent rainfall, as seen in the picture above) and in the southern United States. But in the United States, for example, this helps agriculture rather than hinders it. Hurricanes are less common in the United States and the Caribbean during El Niño, as the air in the Atlantic becomes drier than usual because of the downward flows.

The media began covering El Niño extensively in 1998, when the phenomenon was particularly severe, with, for example, devastating floods in Chile and heavy rains in California.

In general, according to researchers from Cambridge University, the economies of Argentina, Canada, Mexico and the United States «benefit» from El Niño, while those of Australia, Chile, Indonesia, India, Japan, New Zealand and South Africa «lose».

In Europe, the influence of El Niño is much harder to track as it’s farther from the ’epicentre’ and the effects get watered down amid dozens of other factors.

Sometimes (but not always) El Niño is followed by a phase of cooling, La Niña, with completely opposite effects — increased winds at the equator and the movement of warm water to the West Pacific. But often it is a weaker oscillation to the other side, in the process of returning to the global norm. Therefore, the consequences of La Niña are not as serious.

The influence of El Niño does not extend only to the climate — the phenomenon has many indirect effects that are not always easy to trace. For example, it is believed that it was El Niño that caused the famine in Europe at the end of the 18th century, which became one of the incentives of the Great French Revolution.

Therefore, El Niño prediction has become an important field of science — for this purpose, scientists monitor the temperature and pressure in different areas of the Pacific Ocean, use climate modeling and sound the alarm if, for example, it suddenly starts raining in the Peruvian deserts. It is possible to predict El Niño quite confidently in six months, but before that it is very, very problematic.

How El Niño is affected or may be affected by climate change is still unknown — there is no consensus among scientists, because the force of the phenomenon fluctuates in different directions, rather than in any particular one.

Text: Windy.app team

Illustration: Valerya Milovanova, an illustrator with a degree from the British Higher School of Art an Design (BHSAD) of Universal University

Cover photo: Unsplash

You will also find useful

How to read wind barbs — wind speed and direction symbols

How do we measure weather. The complete guide to weather instruments

Latest News

Professional Weather App

Get a detailed online 10 day weather forecast, live worldwide wind map and local weather reports from the most accurate weather models.

Compare spot conditions, ask locals in the app chat, discover meteo lessons, and share your experience in our Windy.app Community.

Be sure with Windy.app.