The fires in California

The fires in California in January 2025 shocked the world. Dozens of people lost their lives, thousands of homes were destroyed, and the economic damage amounted to tens of billions of dollars—all in one of the most developed regions on the planet. How did the fires in Los Angeles start? Is climate change to blame? We will briefly discuss these questions in this article.

California's Climate

The root causes of all weather-related disasters lie in the climate. And for California, the saying «Our strength is in our weaknesses» holds true. Most of the state has a Mediterranean climate, which many consider to be one of the most comfortable in the world. It features warm summers, cool winters without severe frosts, low relative humidity, and moderate precipitation. Summer is almost entirely dry, with most rainfall occurring in winter. For comparison, this climate is also found in Mallorca, Malta, Portugal, Italy, southwestern Australia, and Israel.

Unfortunately, the same characteristics that make the Mediterranean climate so appealing also contribute to California’s long history of wildfires, a problem well-known long before this year’s tragic events.

What Causes Wildfires?

Almost every wildfire results from a combination of two key factors:

- Drought conditions—Dry soil and low humidity make plants highly flammable.

- Strong winds—These help fires spread rapidly, and make them difficult to extinguish.

Let's take a closer look at how each of these factors contributed to the catastrophic fires of January 2025.

Where Has the Rain Gone?

Since the summer months, Southern California has experienced unusually dry weather. And it became especially dry in the fall, when the rainy season should have started. But, in 2024, the area witnessed one of the driest rainy seasons in history.

Precipitation in the subtropics is typically associated with cyclones, also known as lows, which are influenced by the position of the jet streams. Most cyclones develop and intensify at the bends inthe stream.

However, in 2024, the jet stream shifted farther north than usual, altering the usual path of the cyclones. As a result, the cyclones carrying moisture bypassed California entirely, leaving the region in drought conditions. Throughout most of South California, precipitation totals were less than 30% of the norm.

Why did this happen? It’s hard to say! Scientists don’t yet know enough about global weather patterns to pinpoint a single cause. It could be linked to the formation of La Niña, climate change, a series of coincidences, or a combination of multiple influences. Whatever the cause, by January, the air and soil had become extremely dry due to the prolonged absence of rain.

Why were the winds so strong?

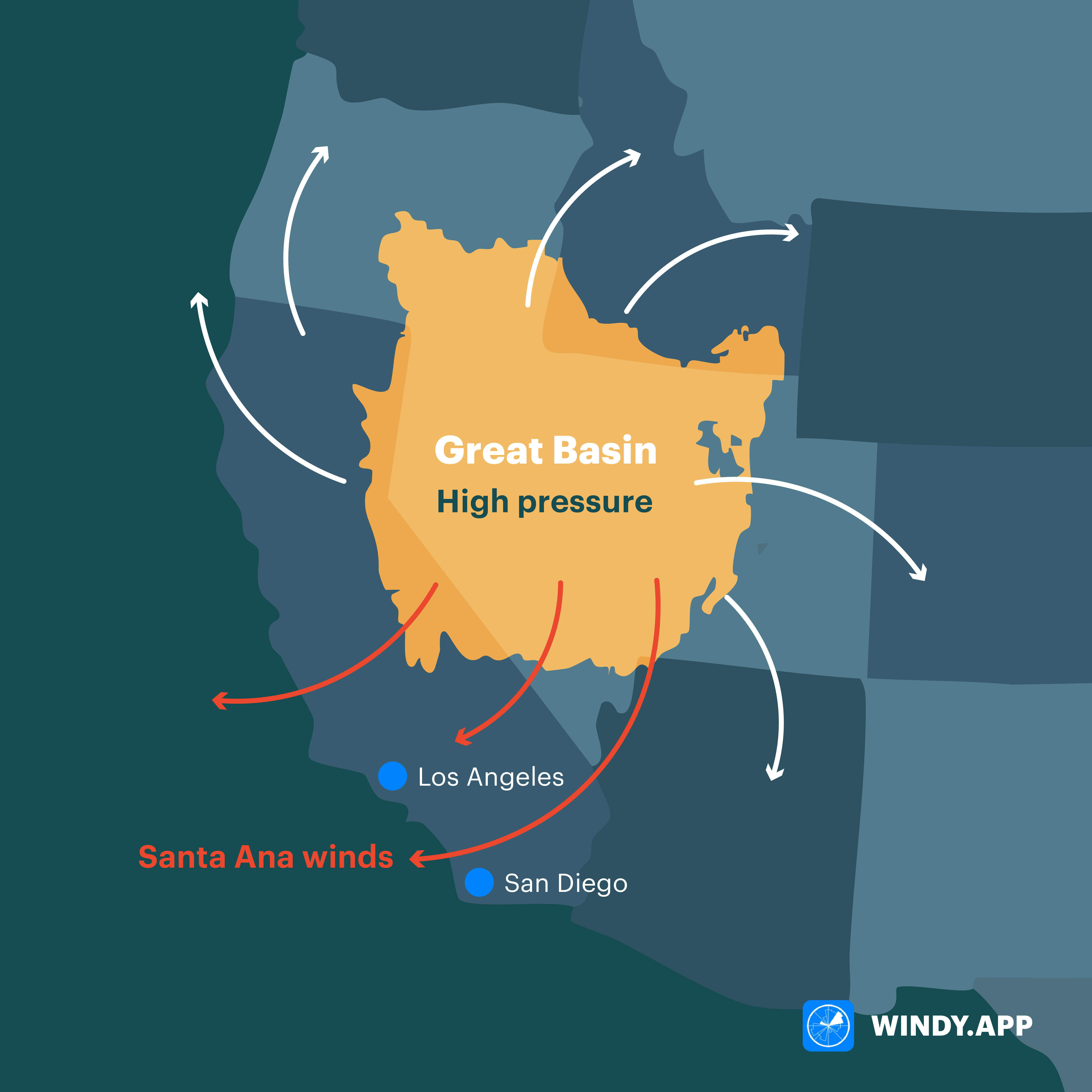

Every year, during fall and winter, the famous Santa Ana winds occur in Southern California. They appear with an anticyclone forming over the Great Basin. The air moves clockwise from the center of the anticyclone (high pressure), and flows towards the Pacific coast. Descending from the mountain passes, the air is subject to adiabatic compression (it warms up and becomes drier).

The figure shows the anticyclone over the Great Basin turning into Santa Ana winds (highlighted in red). Illustration: Valeria Milovanova / Windy.app

The result? The Santa Ana winds become extremely hot, dry, and strong. They can drop in relative humidity to dangerously low levels, and significantly heighten wildfire risks in the region. And if a fire starts, it spreads very quickly.

Has climate change made a difference?

Apparently, yes. And it’s not just about rising temperatures—it’s also about changes in the jet stream. A growing body of data, including historical records, suggests that, as the climate warms, the Pacific jet stream affecting California shifts closer to the north. In the past, it regularly brought cyclones with precipitation, but this is happening less and less often.

Arid regions are among the first to experience rising temperatures and increasing precipitation deficits. This is happening not only in California but also in the Mediterranean, Australia, South and West Africa, and other parts of the world. The fires in California can therefore be seen as yet another troubling sign of climate change. Unfortunately, we are likely to witness more and more of these events in the future.

Text: Eugenio Monti, a meteorologist and a climatologist

Cover photo: Gerson Repreza / Unsplash

Read more:

Latest News

Professional Weather App

Get a detailed online 10 day weather forecast, live worldwide wind map and local weather reports from the most accurate weather models.

Compare spot conditions, ask locals in the app chat, discover meteo lessons, and share your experience in our Windy.app Community.

Be sure with Windy.app.