How lenticular clouds form

This photo was shot above Torres del Paine National Park, Chili. It was picked up by magazines and is even featured on a UFO book cover. There are lots of similar photos in news stories. Is it a UFO? No, it’s a lenticular cloud, also known as a lens cloud. Such clouds don’t move, even in strong winds. In this new lesson of the Windy.app Meteorological Textbook (WMT) and newsletter for better weather forecasting you will learn more about lenticular cloud.

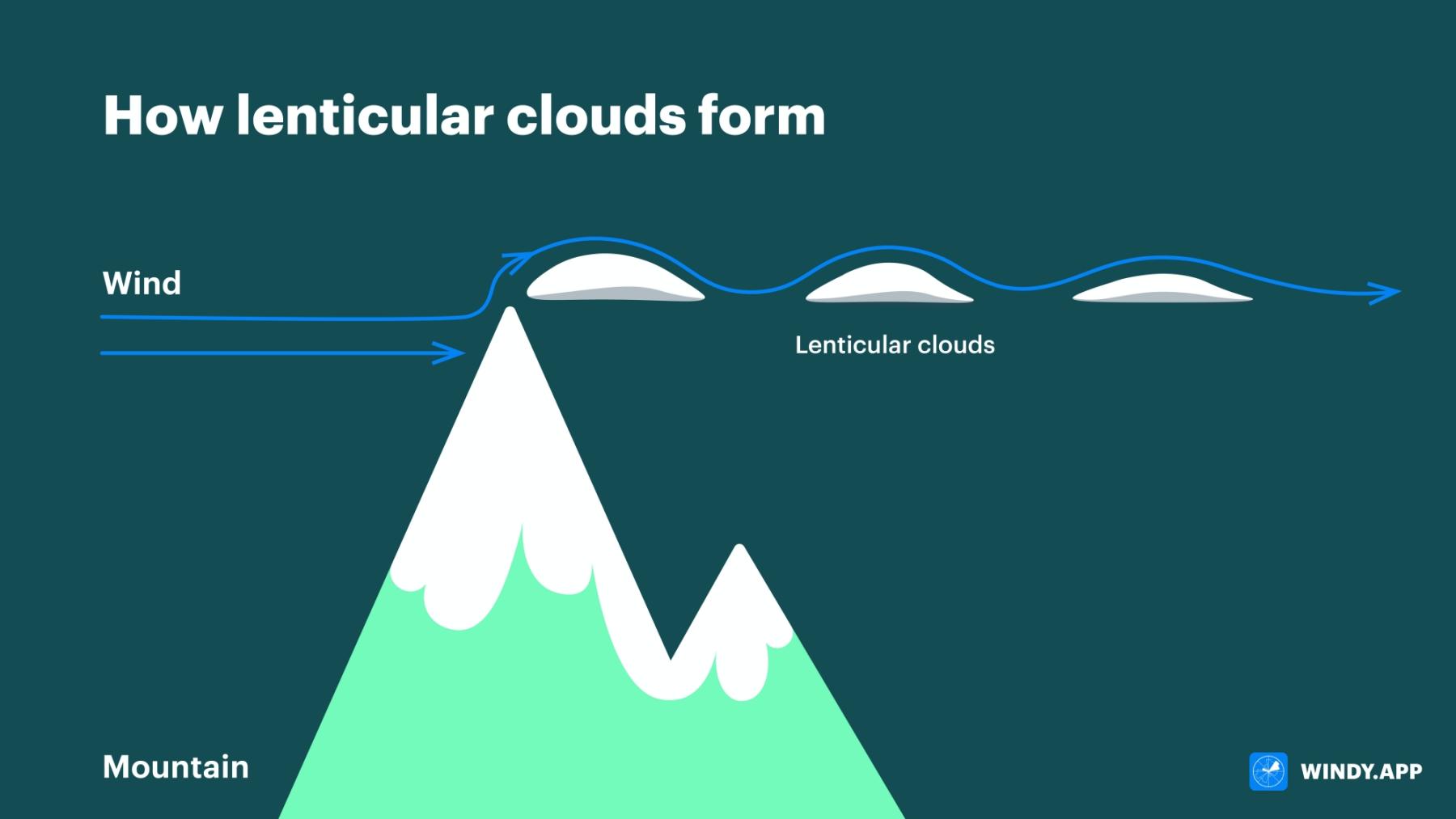

Air as well as water can create waves. Strong wind bumping into a barrier creates an air wave. If you look at a stone on the floor of a current, you’ll see that water goes up a bit in front of it and there’s a ripple beyond.

Air wraps around mountains and after that perturbance starts (an air wave occurs). Just look at the picture and you’ll understand how lenticular clouds appear.

Lenticular clouds above Torres del Paine National Park, Chili. Marc Thunis / Unsplash

Why do the clouds emerge?

The higher air is, the colder it is. When it cools, the moisture it contains transforms into water drops. It’s these drops that form clouds. Thus, a warm air current cools moving up a mountain, creating a cloud.

Why don’t the clouds break?

In fact they do — heavy cold air moves down. Warm humid air replaces it immediately, which turns into drops again. As a result a cloud is always nourished by the air current (air wave).

Why do the clouds stand still?

Because the position of the airwave doesn’t change. The cloud is continually nourished and continually deteriorates. And it looks like it stands still.

The occurrence of these clouds means there’s enough moisture in the air and that there’s a strong horizontal wind of at least 24 km/h.

Lenticular clouds formation. Valerya Milovanova / Windy.app

Text: Windy.app team

Illustration: Valerya Milovanova, an illustrator with a degree from the British Higher School of Art an Design (BHSAD) of Universal University

Cover photo: Lenticular clouds over Torres del Paine National Park, Chili. Marc Thunis / Unsplash

You will also find useful

Latest News

Professional Weather App

Get a detailed online 10 day weather forecast, live worldwide wind map and local weather reports from the most accurate weather models.

Compare spot conditions, ask locals in the app chat, discover meteo lessons, and share your experience in our Windy.app Community.

Be sure with Windy.app.