What is a Föhn

Föhn (the name is also spelled as Fohn, Foehn and Föhnwind) is another mountain wind. It blows from the mountains to the valley and brings very dry and very warm air.

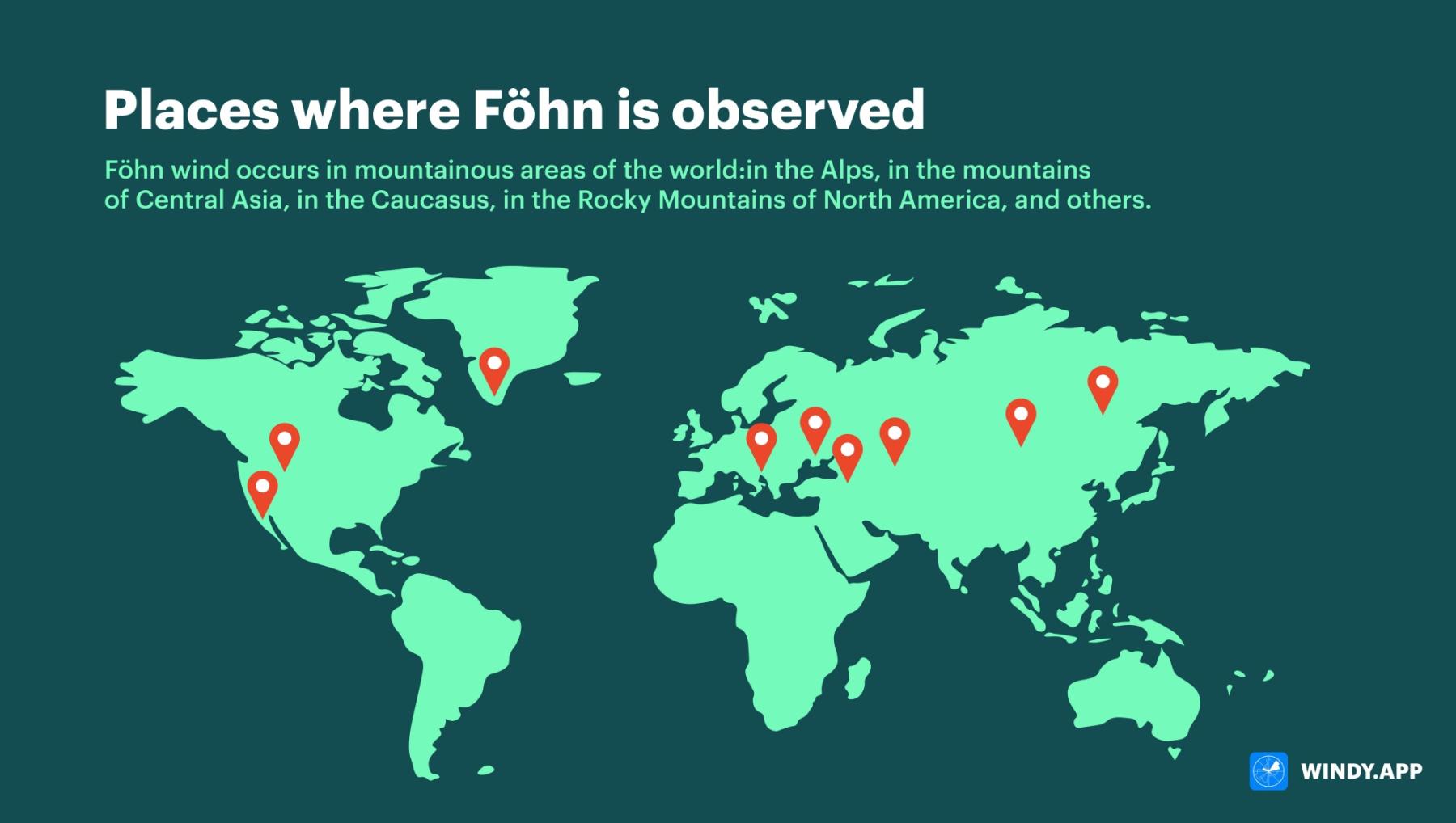

This wind occurs in many mountainous areas of the world: in the Alps, in the mountains of Central Asia, in the Caucasus, in the Rocky Mountains of North America and other places. It is given different names in different places. In the Rocky Mountains of North America, Native Americans call it chinook, ‘snow-eater’, because the snow quickly melts in spring when this wind occurs, leaving dry ground and grass.

Some places where Föhn occurs. Illustration: Valerya Milovanova / Windy.app

How does Föhn form?

Föhn is a bit like bora in its occurrence.

Bora is a strong, cold, gusty wind. It occurs in areas where a low mountain range stretches along the coast of a sea or large lake. Most often occurs in winter. Just as with the bora, with the föhn it all starts with the wind flowing toward the mountains. Only it is not as cold as with the bora. When the air meets the mountains, it is forced upward. While cold, heavy air (in the case of the bora) can only go over a low mountain range, with the föhn, the air can rise to any range height. When the air rises, it cools (we explain why it cools below). As the air cools, moisture condenses in it. Fog (or a cloud) forms. Condensation removes moisture from the air, so that it can then fall as rain or settle on the slopes of the mountains. The result is dry air at the top of the mountain range. When it begins to descend, it heats up.

More about cooling and heating

As the air rises, it works against gravity. This force pulls the air downward, but conditions are such that it does go upward. Nevertheless, the air gives up part of its energy, i.e. part of its heat, to resist gravity. Therefore, the air is cooled as it ascends. To be more precise, the air does not lose its energy, but simply transfers one kind of energy to another. Part of the energy responsible for the temperature of the air becomes the energy responsible for holding the air at a high altitude (part of the kinetic energy is converted to potential energy).

And on the way down? It’s the other way around! When descending from the mountain, the air seems to take back the energy it gave up on the ascent, because now it moves in the direction of gravity. As the altitude decreases, some energy responsible for keeping the air at a high altitude is converted into the energy responsible for the air temperature (potential energy is converted back into kinetic energy).

So, the air is first cooled (while ascending to the top of the range) and then heated (while descending from the top of the range). So the air temperature in front and beyond the range should be the same. But no! The föhn blowing from the mountain is much warmer than the original flow. Why?

Why is it warmer?

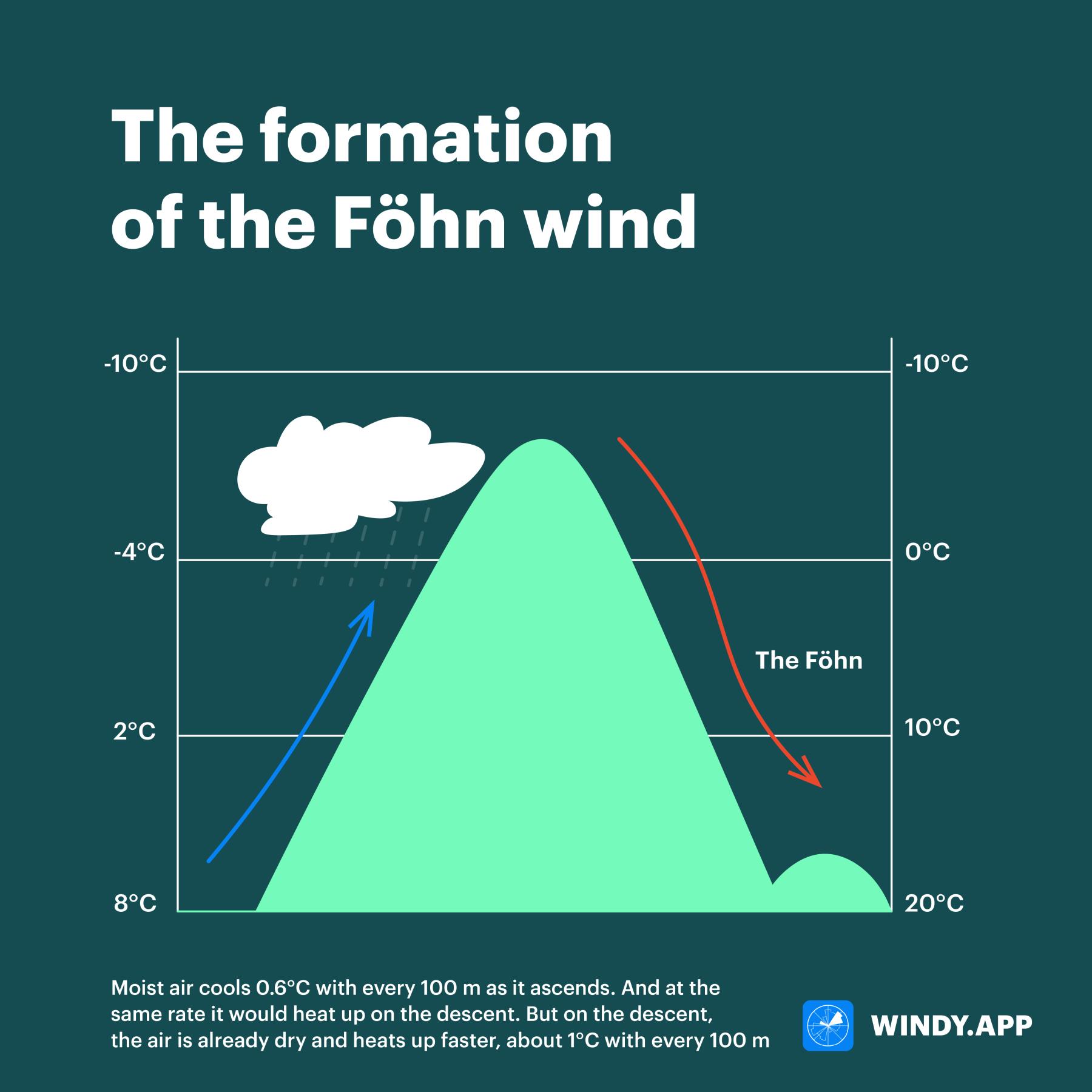

It’s because the air loses moisture as it rises. Moist air cools 0.6°C with every 100 m as it ascends. And at the same rate it would heat up on the descent. But on the descent, the air is already dry and heats up faster, about 1°C with every 100 m. Descending, for example, from an altitude of 2,500 meters, it heats up by 25 degrees. Therefore, the initial wind flow, turning into the föhn, not only becomes dry but also about twice as warm. The föhn usually lasts less than a day, but sometimes as long as 5 days.

Föhn scheme. Illustration: Valerya Milovanova / Windy.app

Consequences

The föhn can cause quite a bit of damage to those who live on slopes and in valleys. In spring, the föhn increases snow melting, which increases the risk of flooding and avalanches. Warm winds cause early budding and flowering, but after the föhn it gets colder and the early buds and flowers die. In summer, the föhn can cause drought and sometimes dries out trees so much that their leaves fall off. Also, it can develop into hurricane force and kill young orchards and vineyards.

Hair dryer?

In German, the word Fön also means ‘hair dryer’, also called Haartrockner.

Text: Windy.app team

Cover photo: Toomas Tartes / Unsplash

You will also find useful

How to read wind barbs — wind speed and direction symbols

Latest News

Professional Weather App

Get a detailed online 10 day weather forecast, live worldwide wind map and local weather reports from the most accurate weather models.

Compare spot conditions, ask locals in the app chat, discover meteo lessons, and share your experience in our Windy.app Community.

Be sure with Windy.app.