What is a thermal column

Skydivers, paragliders and pilots are well acquainted with thermal column. These are ‘bubbles’ or pillars of rising warm air that can reach high altitudes. In this new lesson of the Windy.app Meteorological Textbook (WMT) and newsletter for better weather forecasting you will learn more about what thermal column is.

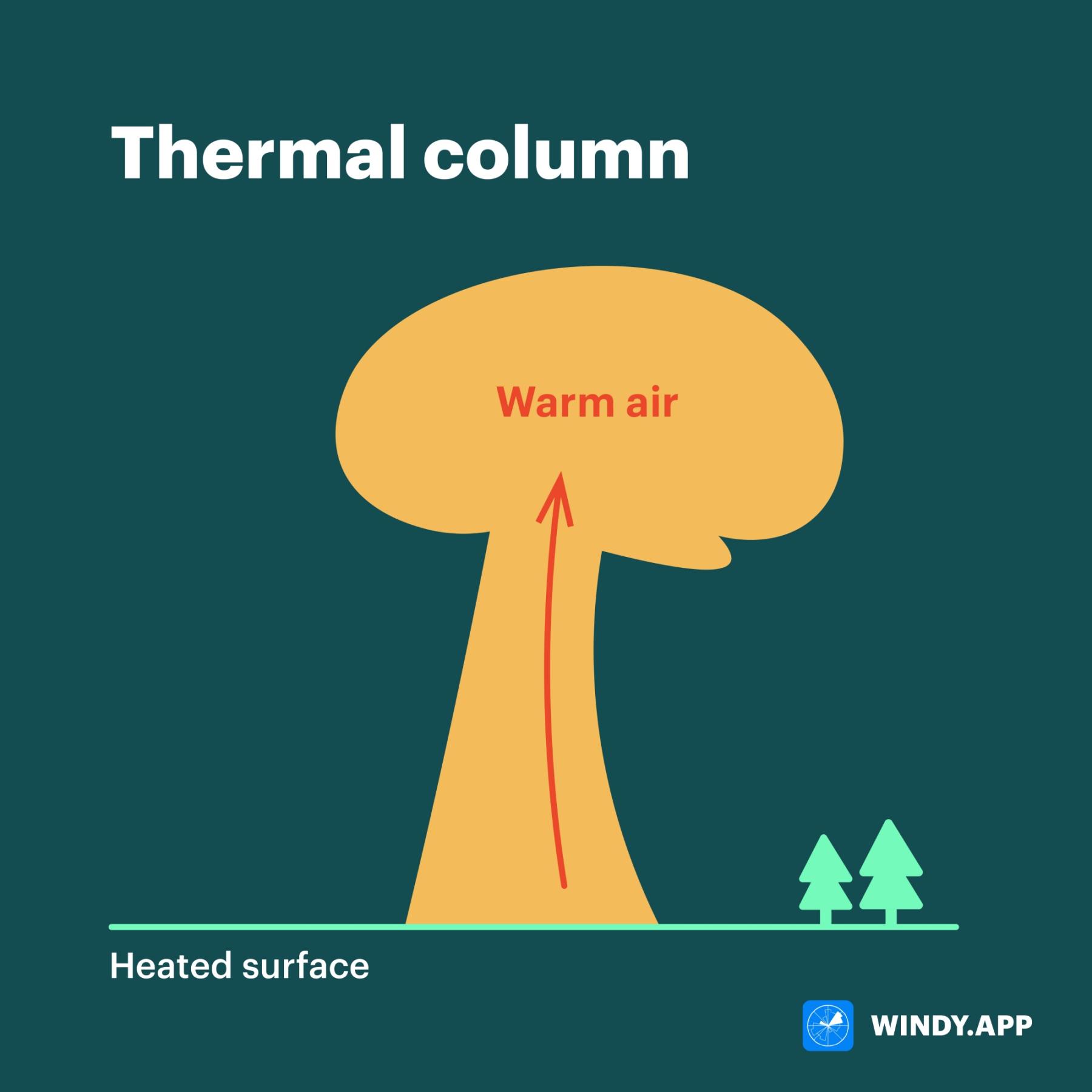

Thermal column

We’ve already mentioned that warm air is lighter and less dense. It always tends to rise and cold air replaces it. A thermal is an ‘accumulation’ of air, in other words. It rises as it’s lighter than the surrounding air.

Sun heating

The surface of the Earth is warmed up by the Sun during the day and the ground heats the air above it.

If the process is slow the warm air will rise in a continuous flow.

If the heating is fast bubbles may occur. They stay on the surface, grow for some time and suddenly tear away.

Thermal column. Illustrations: Valerya Milovanova / Windy.app

Let’s take a pot of water as an example. If it heats up slowly we’ll see a pillar of rising warm water at the bottom. If the heating is intense bubbles are formed.

The surface of the Earth is patchy — the air above the ground will heat up differently at different spots.

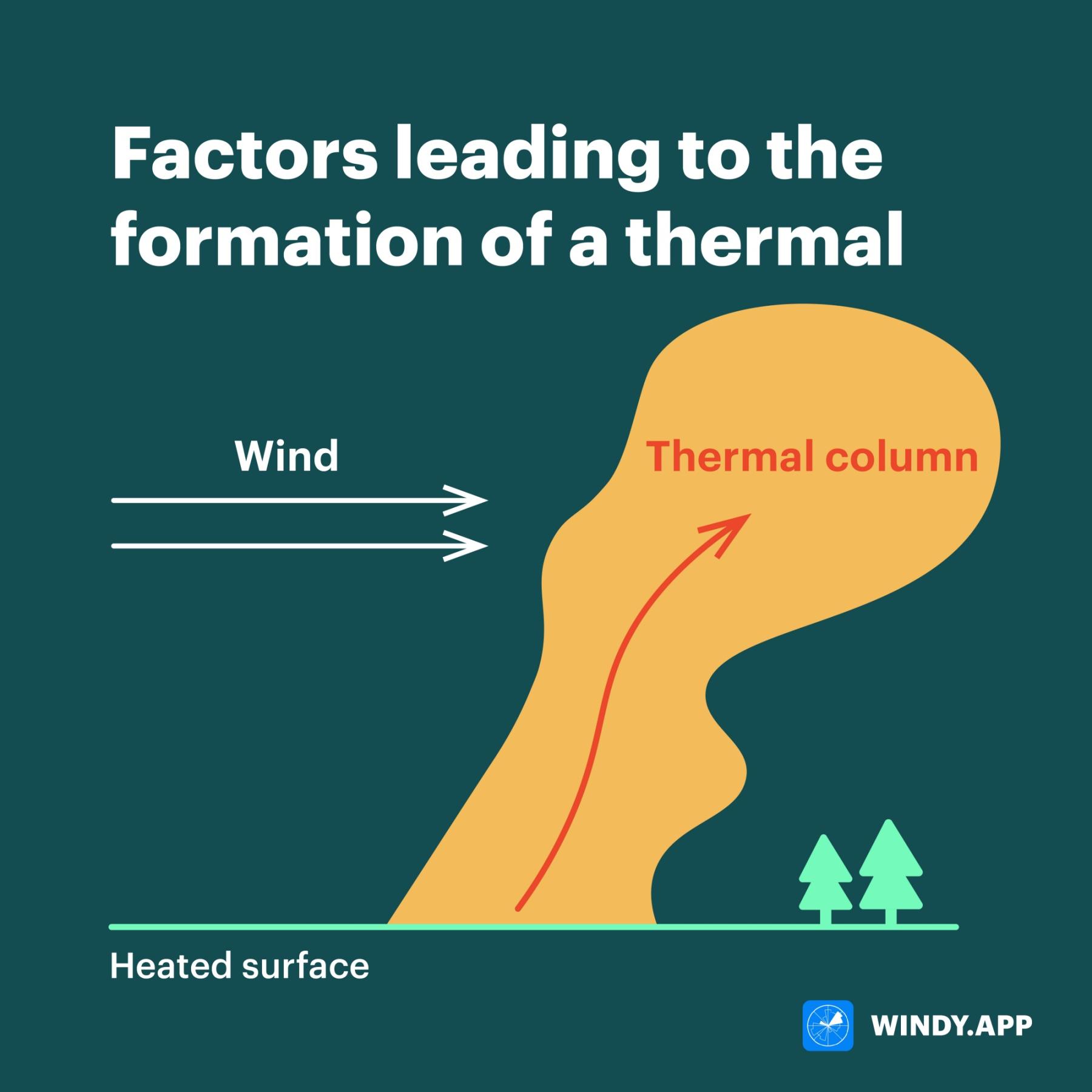

Factors leading to the formation of a thermal:

The more contrast in the weather (cold air — hot sun) — the stronger the thermal columns. In windless weather thermals are almost vertical. If there’s wind the thermal leans in its direction.

Factors leading to the formation of a thermal. Illustrations: Valery Milovanova / Windy.app

Thermals are quite dangerous close to the ground as they cause turbulence for skydivers.

Comment from Windy.app's user Balthasar Wicki:

I am not so sure whether this theory of the development of thermal columns and its upward force is really the state of the current science. It rather reflects the old-fashioned way of looking at thermals which is considered to be outdated for about 4-5 years. The modern science has understood that the engine which keeps a thermal column alive and really is its ‘engine’ is not the temperature gradient (which is much too low and gets countered by the adiabatic cooling due to the expansion of the air while rising) but the gradient in density between the more humid air inside of a thermal and the outside air. The thermal gradient due to convective heating (in the very low level of the planetary ground layer) is only the actuator of a thermal, not its engine.

Your theory would never explain why the really strong thermals form over e.g. lakes and ponds which are less warm than the surrounding earth. However, all glider pilots know this phenomenon. Of course, there are temperature-induced thermals over rocky sides in forests, etc., however, they take their long-lasting energy rather from ingesting the humid air of the forest instead of the rather minuscule differential energy of the thermal bubble which forms as the initial of a thermal.

Also, the dangers of a thermal are not only due to its dynamic force but, under certain scenarios and in certain activities (e.g. ballooning), also due to its differential in density.

Text: Windy.app team

Illustrations: Valerya Milovanova, an illustrator with a degree from the British Higher School of Art an Design (BHSAD) of Universal University

Cover photo: Unsplash

You will also find useful

Latest News

Professional Weather App

Get a detailed online 10 day weather forecast, live worldwide wind map and local weather reports from the most accurate weather models.

Compare spot conditions, ask locals in the app chat, discover meteo lessons, and share your experience in our Windy.app Community.

Be sure with Windy.app.